Let’s go ’round again,

Maybe we’ll turn back the hands of time,

Let’s go ’round again,

One more time.

Average White Band

Were AWB thinking about land reform in Scotland when they dropped that banger? Almost certainly not. Anyway, here I am in 2024 clawing for an original intro to a land reform post, and here we go ’round again, with a further land reform revolution. Maybe we’ll turn back the hands of time.

The much anticipated Land Reform (Scotland) Bill was introduced to the Scottish Parliament on 13 March 2024. The following day, official announcements and reaction started to follow.

On X-formerly-known-as-Twitter, Mairi Gougeon (via the ScotGovRural account) posted a short video explaining she was “really excited” to introduce what she thought would be “a really transformative piece of legislation”. That tweet also provided a link to the Scottish Government news release (and there was a similar LinkedIn post).

I understand all of the 537 respondents to the preceding consultation received an email from Mairi Gougeon expressing gratitude for our submissions; I certainly received an email anyway. For anyone seeking a reminder about that consultation process, I blogged about it prior to submitting my response. You can find the 482 public responses to the consultation on the Scottish Government’s consultation hub, and analysis of some consultation responses in Scottish Parliament Information Centre post from December 2023. That email to consultees, like the news release, explains what the Bill does in the Government’s own (abridged) words.

The four noteworthy paragraphs of the news release are as follows:

The Land Reform (Scotland) Bill… includes measures that will apply to large landholdings of over 1,000 hectares, prohibiting sales in certain cases until Ministers can consider the impact on the local community. This could lead to some landholdings being lotted into smaller parts if that may help local communities.

It will also help to empower communities with more opportunities to own land through introducing advance notice of certain sales from large landholdings. Large landholdings of over 1,000 hectares represent more than 50% of Scotland’s land.

The Bill will also places legal responsibilities on the owners of the very largest landholdings to show how they use their land and how that use contributes to key public policy priorities, such as addressing climate change and protecting and restoring nature. These owners will also have to engage with local communities about how they use the land.

The Bill includes a duty on Scottish Ministers to publish a model Land Management Tenancy which will support people to use and manage land in a way that meets their, and the nation’s, needs. It also includes a number of measures to reform tenant farming and small landholding legislation, providing more opportunities to improve land, to become more sustainable and productive and to ensure that tenants are fairly rewarded for their investment of time and resources in compensation at end of tenancy.

This blog post will offer some initial thoughts on this newest (and third) Land Reform (Scotland) Bill. Before it does that, here are some collected resources (in no particular order, with a mixture of non-partisan and not non-partisan viewpoints):

- A post by the Scottish Parliament Information Centre (aka a SPICe Spotlight) about the proposals for large landholdings;

- An article by Severin Carrell for The Guardian, entitled, “Scottish lairds may be forced to break up estates during land sales“;

- An article by Simeon Kerr in the FT, entitled, “Scottish government introduces land reform bill to boost community ownership“;

- A BBC Naidheachdan report by Calum MacLeòid, featuring interviews with another Calum MacLeòid and someone else who was disappointingly not called Calum MacLeòid (namely Josh Doble from Community Land Scotland) (report and one interview in Gaelic, second interview and captions in English) (a related BBC write-up of this is also available, again in Gaelic). Incidentally, and indeed curiously, there seems to be no English language coverage in the BBC News content for Scotland. There was however a feature on BBC Radio 4’s Farming Today, in the form of an interview with Sarah-Jane Laing (available until 16 April 2024) (more from Sarah-Jane below).

- A column by Calum MacLeod (in English) for the West Highland Free Press, entitled “We are still searching for radical land reform”, an image of which is available on Calum’s Twitter (X).

- A “Thunderer” column in The Times, entitled, “Land reform bill is yet another assault on property rights” (£);

- An article in the Telegraph, entitled, “Humza Yousaf plots crackdown on landed gentry” (£);

- An article in The National, entitled “Scottish Land Reform Bill introduced to Holyrood“, followed four days later by a letter in The National by a correspondent who was not overly enamoured with the Bill;

- An article in Farmers Weekly, entitled, “Outrage as Scots government plans to break up larger holdings“;

- A Bella Caledonia article by Craig Dalzell, entitled, Land Reform Or Another Power Grab?;

- An article by Brian Wilson in the Stornoway Gazette (on 21 March 2024), entitled “Bill gets a muted response”;

- The Scottish Land Commission – the quango established by the most recent Land Reform (Scotland) Act (passed in 2016) – issued a news release to welcome the “meaningful” Land Reform Bill. They have also taken the opportunity to highlight the research and analysis published by Commission in a standalone page on its website.

- A targeted article in the P&J (on the agricultural tenancies provisions (see below)), entitled, “Tenant farmers to benefit from Land Reform Bill“;

- The Scottish Greens have published, in their words, “Everything you need to know about Scotland’s new Land Reform Bill” on their website. The other political party steering this legislation through Holyrood – the SNP – does not have a similar resource on its website as far as I can tell.

- An article by Mairi Gougeon for the Scottish Farmer, entitled “Mairi Gougeon sets out the need for land reform in Scotland“;

- Scottish Land and Estates’ full statement on the Bill is on its website, under the heading “New Land Reform Bill Is ‘Destructive’ Attack On Land Businesses” (£). (They are also feature in various of the articles listed above.) Sarah-Jane Laing, SLE’s Chief Exec, contributed an article to the Daily Mail (headed, “Dangers of this slice and dice attack on private property“), and another SLE Stephen Young bemoaned on Twitter (it’s still Twitter…, okay X) that the Bill was a missed opportunity, would increase bureaucracy, and waste taxpayers’ money.

- Community Land Scotland published a thread (also on Xwitter) where they welcomed the Bill but noted aspects of the Bill need strengthening and bemoaned the exclusion of urban Scotland and community rights to buy from the Bill.

*There may be others (and I know Andy Wightman’s coverage is to come, as at the date of this blog post’s publication on 26 March 2024). I can update this list with any useful coverage from the immediate aftermath, so let me know if I’ve missed anything and I can add it to the list.*

Regarding existing community rights to buy and their general non-appearance in the Bill (save in relation to their interaction with the new Bill’s new features), this can be explained by virtue of a separate review of the various Scottish community rights to buy that was recently announced (on 6 March 2024). No view is offered here on whether this exclusion is the correct approach for this Bill, although for ease (and without meaning to imply a view) this blog post will also exclude existing community rights to buy from its coverage, save where such existing rights inform the new Bill’s provisions. There is quite enough to contend with without that.

Before proceeding, I should also mention the accompanying documents that are served up with the Bill. The accompaniments are:

There is also a Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment to estimate the costs, benefits and risks of the measures in the Bill and, on a more targeted basis, a Strategic Environmental Assessment of Agricultural Tenancies, Small Landholdings and Land Management Tenancy Proposals: Consultation Report. Lastly, the suite is completed with a Delegated Powers Memorandum (which highlights the powers that will flow to the Scottish Ministers) and Statements on Legislative Competence (explaining that both the Presiding Officer and the Scottish Government feel the Bill is within devolved competence).

I won’t rehash all of these documents, although I will highlight certain points of interest from these accompaniments as appropriate. The first thing in that vein is that the Policy Memorandum puts forward the position that all the measures in the Bill comply with Article 1 of the First Protocol to the ECHR (which offers a qualified but important protection to the peaceful enjoyment of possessions) and indeed Article 6 of the ECHR (the right to a fair hearing). You can read about that in paragraphs 286-293. The Presiding Officer and Scottish Government agree.

As readers of this blog will know, in a recent case Scottish Land and Estates (and two other parties) challenged a piece of legislation on various grounds (including with reference to A1P1). Given the expressed views of SLE linked to above and their recent excursion to the Court of Session, this assessment of the human rights compliance of the new Bill might feasibly be put to the test.

Okay, now it’s time to get to my thoughts on the incipient legislation.

DISCLAIMER: This blog post is over 10,000 words long. It is unashamedly one for the purists, albeit I have (honestly) tried to keep things as accessible as I can. As with previous posts on my blog, this post is something of an attempt by me to get my own thoughts straight, and it may form the basis of a future piece of writing and/or be a launchpad for evidence to the relevant committee at Holyrood. Speaking of which, I understand the relevant committee is to be the Net Zero, Energy & Transport Committee. Admittedly, the precursor consultation to this Bill had “Net Zero” in its title, but having read through the new Bill it doesn’t really feel very Net Zero to me, or indeed very Energy or Transport.

SECOND DISCLAIMER: Yes, this is all quite political, and some of you might even be reading this blog post in the hope I nail my colours to a particular mast. For the most part, I have tried not to do that (some people may not believe me, or think I have not done this particularly well – so be it). What I have tried to do is set out what the Bill appears to do, and offered some thoughts here and there.

Now it really is time to get to the new Bill.

The Bill – a structural overview

The Bill is in two substantive Parts. The first is called “Large land holdings: management and transfer of ownership”, and it seems fair to say Part 1 has attracted most of the attention so far. Part 2 is called “Leasing land”. Unsurprisingly, this second Part contains provisions around certain landlord and tenant relationships. There is also a Part 3 with “Final provisions”, allowing for relevant regulations to be made, dealing with commencement matters, and conferring the Bill its short title (which includes the year “2025” – so let’s not expect the Bill to be passed in the next nine months). Finally, there is a Schedule which hooks into Part 2’s “Leasing land” provisions. I’ll return briefly to Part 2 at the end of this post.

Part 1 – Large land holdings: management and transfer of ownership

We already have coverage of this Part of the new Bill in the excellent analysis in the abovementioned SPICe post. I’ll try to make my coverage suitably different to that so that this post can be read as something of a partner piece. There are also some aspects that need to be detailed here to set the scene, and to allow this post to stand on its own two feet.

Part 1 of the Bill brings in something innovative for modern Scottish land reform, in that individual proprietors can be subjected to different regimes based on the amount of land that they own. The nearest thing we have had to such differential treatment for owners based on a broad categorisation was in relation to the community right to buy as originally enacted. Part 2 of the 2003 Act was restricted to rural areas only, defined with reference to the local population (the relevant threshold being 10,000 in a settlement). That restriction was swept away by the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015, and in any event related to the happenstance of how many folk lived in an area. Be that as it may, since that reform all owners, big and small, urban or rural, were treated in similar terms in that they could all be in the crosshairs of a right to buy application. Now, we are moving towards actively targeting any owner who has a certain amount of land. As we shall see, there are separate trigger points for the different innovations that are being introduced.

The “Large land holdings: management and transfer of ownership” content in Part 1 is subdivided into four aspects. The first relates to an obligation on owners of large land holdings to engage with the community, by way of a suitable land management plan. The second relates to giving certain community groups a chance to intervene when a large land holding is to be transferred. The third relates to “lotting” of large landholdings, which will delay the transfer of certain large land holdings until Scottish Ministers have decided whether the land should be transferrable only in parcels as specified by Ministers and in turn prevents any transfer not in accordance with that decision. The fourth relates to a new Land and Communities Commissioner, being a new Commissioner for the Scottish Land Commission.

Community-engagement obligations in relation to large land holding

Section 1 is headed “Community-engagement obligations in relation to large land holding”. This section shunts thirteen new sections into Part 4 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016. Part 4 of this preceding Land Reform Act has, until now, only contained a single section, encouraging owners of land to engage communities in decisions relating to land when such decisions may affect. Part 4 will now be divided into two Chapters: the first now has a new title – “Community-Engagement Guidance” – and the second will be headed “Community-Engagement Obligations in Relation to Large Land Holdings“. Why the final word in this Chapter heading is pluralised while the final word in the heading of the section in the Bill is not is not clear.

Anyway, turning to more important matters, the new section 44A of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 empowers the Scottish Ministers to pass regulations that impose obligations on the owner of land for the purpose of promoting community engagement in relation to the land. It is ordained that such regulations must be in accordance with new sections 44B and 44C (more on those below), and secondly that those obligations can only apply to land that is caught within the definition in a new section 44D. (I’ll not labour the “new” section terminology from here on in, but will include it from time-to-time for clarity.) Next, any regulations are to be informed by the land rights and responsibilities statement.

It will be recalled that the LRRS was introduced by the 2016 Act. It will also be recalled that there was much chatter about the LRRS being beefed up in the consultation that preceded this Bill. It is accordingly slightly surprising that this is the only mention of the LRRS in the new Bill.

Finally, section 44A provides that the Scottish Ministers must consult the new-fangled Land and Communities Commissioner before passing any regulations. More on the new Land and Communities Commissioner below too, but the significance of this office for section 44A is that it will need to be created and then filled (at least on an acting basis) before any regulations can be passed, meaning it will be a little while before any of this can bite.

Section 44D sets out the “Land in relation to which obligations may be imposed”. In a broad sense, land can be lassoed in one of two ways, namely by (a) exceeding 3,000 hectares in area, or (b) forming part of an inhabited island in some circumstances. The criteria by which land forming part of an inhabited island will be caught are where the land (i) exceeds 1,000 hectares in area, and (ii) comprises more than 25% of the land forming the island (that term being construed in line with the Islands (Scotland) Act 2018). That is to say, where you have a holding that makes up a quarter of an inhabited island, it need only be 1,000 as opposed to 3,000 hectares.

In the preceding consultation there was discussion about data zones and local authority wards (where they were classified as an Accessible Rural Area or Remote Rural Area) being alternative ways of determining if land was caught. For better or worse, there is no mention of these in the Bill.

The footprint of a mainland or island holding is not the end of a story though. Such land can be a “single holding” or a “composite holding”.

A single holding is defined as the whole of a contiguous area of land in the ownership of one person or set of persons. By contiguous area of land, it is meant that all the land is connected, and you can go from one point on that holding to another point there without crossing another person’s land; that is to say, the land is somehow touching. The other point from this definition is there can be single (exclusive) ownership or co-ownership (shared with other people) of a single holding. Where such a single holding clears the 3,000ha (or 1,000ha for suitable islands) threshold, the land holding is caught.

The Bill goes on to say that one single holding (“holding A”) joins up with another (“holding B”) as a composite holding if certain conditions are met, and that a composite holding may consist of any number of single holdings.

The conditions start with a requirement that a boundary of holding A touches a boundary of holding B. There is then a further requirement of some kind of connection between the owners of each holding. This will be so when the owner of holding A is either:

(i) also the owner of another single holding that forms part of a composite holding of which holding B forms part, or

(ii) connected to the owner of another single holding that forms part of a composite holding of which holding B forms part.

I’ve quoted that verbatim. I confess, I found it quite tricky to render it in any other way. There’s more to consider though, in terms of what is meant by connection. This is defined such that one person is connected to another person if: they are both companies in the same group in terms of tax treatment (under the Taxation of Chargeable Gains Act 1992); one has a controlling interest in the other (in terms of regulations made under section 39 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016); or a person holds a controlling interest in them both.

If you’re finding this a little confusing, I think that’s understandable. It took me blogging to get my head around it all. One further clarification of what is meant might come from the Explanatory Notes, as follows:

For example, if A Ltd and B Ltd are part of the same company group and A Ltd owns 2,000 hectares adjoining B Ltd’s 2,000 hectares, the combined single holdings of A Ltd and B Ltd would be treated as forming a 4,000 hectare composite holding. [Community-engagement provisions] would apply to the land comprising that composite holding, and therefore regulations could… [impose] obligations on both A Ltd and B Ltd in relation to that land.

Paragraph 18

To expand on this example, if A Ltd owns 2,000 hectares adjoining B Ltd’s 2,000 hectares to the west and also owns 500 hectares adjoining B Ltd’s 2,000 hectares to the east, all 4,500 hectares would be caught.

To offer a further elaboration, if A Ltd, B Ltd and C Ltd are all part of the same group, and A Ltd owns 2,000 hectares adjoining B Ltd’s 2,000 hectares to the west, and then C Ltd owns 500 hectares adjoining B Ltd’s 2,000 hectares to the east, again all 4,500 hectares would be caught.

One final point about the land which can be caught by land management planning. Section 44M allows Scottish Ministers to modify the land in relation to which obligations may be imposed. Regulations are actually to be made under section 44A, but this change would presumably be effected by amending section 44D (a point borne out by the explanatory notes at paragraph 20). There may be a drafting reason for referring to section 44A rather than 44D but my inclination is that the provision that is being changed should be referred to (either in addition to or in substitution for the other provision). To refer to section 44D directly would also seem to align with the approach in new section 46L (in relation to the large land holdings that can be subject to an extended opportunity to register a community interest in land – more on that below). This is to say nothing about whether this scope should be amendable by regulation; that’s an argument for others to run.

Okay, so your land holding is snared by this regime. What next? Regulations, that’s what; this goes beyond the warm and fuzzy guidance to land owners that was initially provided for by the previous Land Reform Act (albeit that guidance stands, for land holdings of all shapes and sizes). When the regulations come to be made, they must require certain things of affected owners, as set out in two sections.

In terms of the new section 44B, those regulations are to include provision that the owners must ensure: (a) there is a publicly available land management plan in relation to their land, (b) there is engagement with communities on the development of, and significant changes to, the plan, and (c) the plan is reviewed and, where appropriate revised, before the end of each period of 5 years beginning with the day on which the latest version of it was made publicly available. The italicisation in point (b) above is mine, and no doubt stakeholders will be keen to ascertain exactly what all these terms mean. Section 44B goes on to say that any obligation that is brought in need not be a blanket obligation for all section 44D land, and further describes what information a land management plan is to contain. Some of these are general, such as the owner’s long-term vision and objectives for managing the land (including its potential sale), and how the owner is managing or intends to manage the land in a way that contributes towards adapting to climate change and increasing or sustaining biodiversity. Others specifically hook into existing legislation and related guidance, such as the Scottish Outdoor Access Code and the code of practice on deer management flowing from the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 and the Deer (Scotland) Act 1996 respectively, and the net-zero emissions target set by the Climate Change (Scotland) Act 2009.

One other feature that must be in the regulations is stipulated in section 44C: the owner of any affected land will be obliged to consider any reasonable request from a community body to lease the land (in whole or in part). The regulations may sculpt the land that is to be subjected to this obligation to consider, but nevertheless this will be an interesting development, and could put community bodies dealing with large landowners on a similar footing to community bodies seeking a community asset transfer from a public bodies (in terms of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015). Incidentally, community bodies here is already defined, with reference to the first Land Reform (Scotland) Act (meaning this obligation to consider will only relate to requests received from suitably incorporated and endorsed community bodies).

Obligations only matter when they can be effectively enforced, so that is the next thing to consider. A breach of any obligations falls within the remit of the newfangled Land and Communities Commissioner. The LCC may investigate alleged breaches and, if a breach is identified, a sanction can follow. There are some catches though. First, the LCC cannot take the initiative here: it cannot act of its own motion. Second, only certain persons can report an alleged breach of any obligations. Three statutory “quango” organisations are worth mentioning first, as they have a Scotland-wide role and as such can clype about any apparent breaches. These are Historic Environment Scotland, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency, and Scottish Natural Heritage (aka NatureScot, which has been referred to by its (still correct) legal name). Next, a local authority can be a clype, but only if the land to which the report of the alleged breach relates falls (wholly or partly) within its area. Finally, a community body in terms of Part 2 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 that has registered a community interest in the land to which the report of the alleged breach relates (or is eligible to do so) can be a grass. All of this is to say that punters cannot directly go to the LCC: either they have to convince someone at their council or a suitable quango to do it for them, or they will have to have jumped through at least some of the community right to buy hoops.

The logic behind this might be related to managing the new Commissioner’s in-tray, or ensuring there is not an immediate glut of spurious complaints, or indirectly creating a quality filter by only allowing organisations with a certain capacity to clype. No doubt this will be a point of discussion as the Bill goes through Parliament. For now though, it can also be noted that new section 44M allows this list of clypes to be amended by regulation; this could either restrict or expand the list, but it would nevertheless remain a closed list.

[Section 44M appears to have a slight error in formatting, where a rogue subsection (5) appears, plus there is no direct mention of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 that I assume is the target of the amendment to allow regulations under the new provisions to be made under the affirmative procedure. Hopefully this will be picked up.]

Assuming that the Land and Communities Commissioner receives a valid report (containing details of the alleged breach and signposting the provision of the regulations imposing the obligation that is alleged to have been breached), the LCC may investigate. The LCC must be satisfied sufficient information has been included to proceed to an investigation and also that there has not been a substantially similar report by the same person for the same person already, Further information can be sought if that is felt appropriate. The LCC may thereafter decide not to investigate if further information is not forthcoming, or if making a request for any information would be unlikely to flush out any relevant info. If the LCC does decide to investigate, this will be notified to the relevant parties (including the person who may have breached the obligation), and further information can be sought during any investigation, with a financial penalty for non-compliance with any request for information of up to £1,000.

Should the LCC determine, after an investigation, that there has been a breach, a fine can be imposed, up to a maximum of £5,000. This will only happen where: (a) the person that committed the breach has been given an opportunity to make an agreement with the LCC about what the person must do to remedy the breach and there has either been no agreement or a failure to fulfil any agreement, or (b) the LCC does not consider it appropriate to give the person that committed the breach an opportunity to remedy it because of that person’s previous failure(s) in this area. Anyone fined has 28 days to appeal to the Lands Tribunal for Scotland on the basis the imposition of it (a) was based on an error of fact, (b) was wrong in law, or (c) was unfair or unreasonable for any reason (for example because the amount is unreasonable). The final provisions pertaining to this regime relate to confidentiality and where any ingathered fines go (to the Scottish Consolidate Fund).

The levels of fine here are not exactly stratospheric – for example, an unregistered private residential landlord can face a fine of £50,000. Be that as it may, it should be acknowledged that moving from a system that involved no fines at all to any fines is always a shift. I do ponder whether it might have been worth allowing the levels of fine to be changed by future regulation (although there may be some criminal law consideration that stops this from being suitable).

Finally, it is worth pondering what these fines might be for as things stand. The regulations under section 44B need only relate to having a management plan, but that provision says nothing about the need to cater for breaching a management plan. The only continuing obligation that must be included in any regulations is a duty to consider a reasonable request for a lease from a community body, but provided a land owner does indeed consider such requests they can otherwise be passive (unless and until the regulations go further than the terms of the statute). Accordingly, any sanction for the owner of a large land holding failing to meet what is in their land management plan will more be about negative publicity than strict legal consequences.

Community right to buy: registration of interest in large land holding

Sections 2 and 3 of the new Bill tinker with the community right to buy provisions found in Part 2 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003. This is the scheme that confers a right of first refusal to eligible community bodies who have registered a community interest in land in a public register maintained by Registers of Scotland. Normally, steps need to be taken by a community suitably in advance of the land they are targeting being exposed for sale, albeit there are some provisions for a “late” application.

To save space, I won’t explain what those late application provisions are in detail, but essentially late applications are put through more of a wringer than non-late applications. For example, standard applications only need to be gauged as being in the public interest, but for late applications the factors bearing on whether a community’s scheme is in the public interest need to be strongly indicative of that being the case. Meanwhile, standard applications need to have a level of community support sufficient to justify a scheme being allowed to progress, whereas late applications need to have a “significantly greater” level of support than that. Also, even if you can meet these more onerous tests, there is a requirement that a community body has undertaken such relevant work or taken such relevant steps as Ministers consider reasonable prior to the land being exposed for sale. This can be a complicated provision to follow, but suffice it to say that the new Bill allows for much of the procedure to be side-stepped for large land holdings in suitable circumstances (although there will still need to be healthy support and a strong indication of the application being in the public interest, by virtue of those two requirements being applied by a different means).

Section 2 of the new Bill introduces 13 new sections to Part 2 of the 2003 Act: a new section 39ZA to take care of replacement procedural requirements; and twelve new sections in a new Chapter 2A, with the subheading “Extended Opportunity to Register Interest in Relation to Large Land Holding”. Before you ask, yes, section 1 of the new Bill amends the 2016 Act, whereas section 2 of the new Bill amends the 2003 Act. Statute navigation skills are going to be needed to make sense of everything by the end of this reform process.

A new section 46K of the 2003 Act introduces a threshold value that the new regime can apply to. It does this in a similar way to the land management plan provisions (allowing for single holdings and composite holdings), but with one fundamental difference: the area stipulation is simply that a large land holding exceeds 1,000 hectares (i.e. “smaller” mainland estates of 1,000-3,000 hectares are caught).

Any community seeking to acquire land through Part 2 of the 2003 Act and dealing with a 1000ha+ parcel of land can now make use of a brand new regime, where they are invited to do so by Scottish Ministers. With that in mind, section 46A provides that Scottish Ministers are to keep a list of the contact details of persons who wish to be told about any possible transfer of a large land holding in a particular geographical area. Such persons (along with relevant community councils, local authorities and national park authorities (if applicable)) then must be told of transfers of suitable land in the relevant area, as set out in section 46D(2)(b). The consultation had suggested that local registered social landlords (aka housing associations) might also be tipped off here, but they have not made the cut.

The starting point for this scheme is section 46B, which introduces a (temporary) prohibition on the transfer of affected land, to allow time for interest to be registered by a community body. The owner and, if relevant, a secured creditor with a standard security (commonly referred to as a mortgage) is barred from selling the land to allow eligible community bodies additional time and opportunity to submit an application to register an interest in the land. As the Explanatory Notes explain (at paragraph 35), this is an additional option for certain community bodies, and the existing late application procedure under section 39 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 remains open to community bodies in relation to land that is a large holding of land (or part thereof) should they not be invited to submit an application under new section 46G or if such an application is somehow unsuccessful.

If an owner of a large land holding (or a secured creditor with a right to sell that land) wishes to transfer it, they must apply to the Scottish Ministers for permission via a prescribed notice. Ministers will then publicise this wish (in accordance with new section 46D), by arranging for prescribed information about the possible transfer of the land to be made publicly available on a website and sending the prescribed information about the possible transfer of the land to those detailed on their section 46A list and the other interested entities listed above. When they have done this, Ministers are to notify the person wishing to transfer the land that the section 46B(1) (temporary) prohibition is lifted once the period of 30 days beginning with the day that Ministers fulfilled their publicity duty regarding the possible transfer of the land has expired, but the section fudges this by saying if they are still considering matters when the period expires they should not give any notice until the have reached a decision as to whether they should impose a (further) prohibition in line with section 46F.

This further prohibition on transfer – which lasts for 40 days – can kick-in when: (a) Ministers have publicised the possible transfer of the land, or a larger area of land of which it forms part, in accordance with section 46D; (b) a person has submitted to Ministers a suitable note expressing an intention on the part of the person, or another person, to register a community interest in the land (called a “note of intention to register”); (c) the note of intention to register was received within 30 days of the Ministers sending information about the possible transfer in accordance with section 46D(2)(b); and (d) Ministers are satisfied that, before the expiry of this extra prohibition, it is likely that an application to register a community interest would be made in line with the note of intention to register and that there is a reasonable prospect of that application resulting in a community interest in the land being registered. That is to say, this extra prohibition should only be allowed when someone has given a suitable, timeous notice of intention to register AND it is likely that this can be followed by a full and plausible registration application. (This is not an easy provision to read, or indeed explain.) A further subsection allows for the prompt incorporation of the legal entity that will in fact be the community body that is to come to own the land.

Any transfer in breach of any prohibition is of no effect, unless one of the existing exemptions in section 40 of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 applies. This allows for “transfers otherwise than for value” to take place (the SPICe blog post gives the examples of transfers between spouses, and transfers between companies in the same group, and you could also add a transfer on inheritance). There also some specific exemptions, such as a transfer as a result of a divorce or separation agreement. A specific provision (section 46I) allows for the prohibition on transfer to be lifted by Ministers in exceptional circumstances, such as to alleviate, or avoid, financial hardship. (A similar safety valve exists in relation to forced transfers of croft land to a crofting tenant when this would cause the landlord a substantial degree of hardship.) Any lifting of the prohibition can only follow on from a suitable application by the owner of the land.

That concludes this new right for a community to gatecrash a sale of a large land holding, save for the technical amendments found in section 3 of the the new Bill. This section modifies three statutes to ensure the new regime is compatible with the Conveyancing and Feudal Reform (Scotland) Act 1970 (regarding the enforcement of standard securities), other provisions of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, and the Land Registration etc. (Scotland) Act 2012 (to allow the Keeper to flag any attempts to register a transfer that does not take account of the new regime to the Scottish Ministers).

This new scheme could, theoretically, allow a well-organised and well-resourced community to acquire the whole area of a large land holding if all the stars align. As the Explanatory Notes acknowledge, though, it “will more usually be the case” (at paragraph 32) that part of a large land holding could be hived off from another transfer. The usual community right to buy valuation provisions would then still apply. Current market rates may make it difficult for some communities to find the funds needed, and as such we now turn to the next set of provisions that are not predicated on community action: compulsory lotting.

Lotting of large land holding

Section 4 is headed “Lotting of large land holding”. It deposits a brand new Part 2A into the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, which contains 23 sections (running from 67C to 67Y – section numbers 67A and 67B were already taken by new provisions inserted by the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015). New Part 2A is headed “Lotting of large land holdings”. Why the final word in the heading of this Part is pluralised while the final word in the heading of the section in the Bill is not is not clear.

This is the biggest of the new substantive schemes that is inserted by the new Bill. It is also pretty innovative in terms of Scottish land reform, in that it is in no way predicated on a community proactively taking action. That is not to say that this new Part 2A is a community free zone, but is noticeable how rarely the word “community” appears in this Part given the previous approach to Scottish land reform. (The word “community” only appears in section 67N and indirectly in section 67O, but more on that below.) I’m conscious this is already a mega-blog and I will accordingly keep my coverage of the lotting provisions focussed. If there is a clamour for more coverage (which, I grant you, seems unlikely), I may revisit this content.

What does this new scheme do? Like the provisions just mentioned, they can prohibit a transfer of a large land holding in certain circumstances. Also like the extended community registration of interest provisions, these can bite in relation to a threshold figure of 1,000ha, but there are some other considerations as well. The land affected by the prohibition is set out in section 67G.

The first possibility of a land parcel being caught by the provisions is simply that the area to be transferred exceeds 1,000ha in area. A second possibility comes to the fore when a parcel of land to be transferred exceeds 50ha in area and various other criteria are met, including that it forms part of a large holding of land and that there is a plan to transfer another part, or parts, of the large holding (and suitable notice under the land reform legislation has been given). In that situation, the overall picture is then looked at to gauge whether the combined area of the first parcel of land and the other part(s) of the large holding that are to be transferred exceeds 1,000ha (disregarding from that total any area in respect of which a contract has been concluded since any initial notice of intention to transfer was given).

Section 67H offers some further detail about what a large land holding means, setting out once again the familiar scheme for single holdings and composite holdings. There is an error in the new Bill here, with subsections (2) and (3) incorrectly cross-referring to each other. Hopefully this will be picked up. Sections 67I and 67J bring in familiar details about connected persons (tracking the other provisions in the new Bill) and exempt transfers (like other provisions in the new Bill, drawing on the existing 2003 Act exemptions).

With that overview of what the rules can and cannot apply to, we now return to what the rules are. Section 67C provides the first prohibition: thou shalt not transfer land if section 67G applies, the transfer is not exempt, and where there is no lotting decision in effect in relation to the land. Section 67D provides the second prohibition: thou shalt not transfer land where a lotting decision is in effect unless the transfer is exempt or the transfer is taking place in accordance with that decision or with Ministerial approval. Further provisions in section 67D explain that a transfer cannot take place of an area that does not correspond with a lot specified in a lotting decision, and that a transfer that would result in the same person or connected persons owning more that one of the lots specified in the lotting decision that will be of no effect.

This leads inevitably to the question, “what is a lotting decision”? This key concept is introduced in section 67F. With reference to the following sections of 67M, 67N and 67R, it is explained that a lotting decision is a decision by Ministers about whether land is to be transferred in lots. It is also clarified there that any references to lotting decisions relate not only to the whole area of land but also to any part of that area. There is then some wording about when a lotting decision comes into effect (the next day if no lotting is needed, and a little later if it is decided land may only be transferred in lots, depending on whether there is an appeal or not), and when a lotting decision is to cease having effect. This will happen when the land is transferred in compliance with the decision (i.e. to someone not connected to the transferor), when there is a successful appeal to the Court of Session (that’s right, straight to the top; no Lands Tribunal for this appeal), if the decision is withdrawn after a review by Ministers, or when the decision expires. Expiry is normally after five years, but it can be after one year when a land owner has pressed for an expedited decision owing to their financial hardship (more on that below). These time periods can be changed by regulation.

Attention then turns to section 67K, and Ministers’ duty to make a lotting decision. Normally this will happen when they receive a valid application from the (outgoing) land owner, it being recalled the first prohibition will prevent this from happening unless there is a lotting decision in place. The other occasion where Ministers will have a duty to make a decision is when something comes back to their desk after a successful appeal. For most land, an application will be valid if it is made in the prescribed manner by the owner of the land in respect of which the application asks for a lotting decision, or the owner of part of that land where a composite holding is in play, or by a secured creditor (if relevant). The other thing to consider though is whether an existing lotting decision might derail any (further) application, because section 67K(2)(c) provides that a valid application cannot relate to that is (in whole or in part) already subject to a lotting decision or where another application asking for a lotting decision is being considered.

Certain unorthodox situations are then catered for, with Section 67L allowing anyone entitled to ask for a lotting decision in the first place to then ask the Ministers to stop their consideration. Section 67M then deals with the aforementioned expedited lotting decision where an owner is facing financial hardship. This allows Ministers to decide that land need not be transferred in lots if they are satisfied that the owner of the land in question wants to transfer it in order to alleviate, or avoid, financial hardship, and waiting for a “standard” lotting decision (under section 67N) is likely to cause, or worsen, that financial hardship.

Turning now to section 67N, this provides that Ministers may make a lotting decision with the effect that land may only be transferred in set parcels of land rather than en bloc to a single person only if they are satisfied that this new ownership jigsaw would be comparatively more likely to lead to the land being used in ways that might make a community more sustainable. Assuming this is thought to be the case, the lots must be specified in the lotting decision. Where Ministers decide not to make a lotting decision, they will nevertheless make a lotting decision stating that the land need not be transferred in lots. Before making any lotting decision, Ministers are to request (and take into account) a report under section 67O in relation to the land. The production of such reports is a further role of the new Land and Communities Commissioner, and the only steers in section 67O about what the LCC will have to do is the need to prepare a report in accordance with any instructions given by Ministers, and that a report is to inform the Ministers. Finally, section 67N says that Ministers must have particular regard to the frequency with which land in a given area becomes available for purchase on the open market and the extent of ownership concentration in a given area when considering the effect that a decision stating that land may only be transferred in lots might have on a community.

This is something of a shift away from the public interest test that the consultation adverted to. As noted above, it is also not quite in-keeping with the tendency of earlier legislation for a community to take proactive steps. It does however introduce the community at a one-step-removed level, such that it is a decision is solely to be informed by the sustainability of a community. Presumably where there is no resident community there will be no scope for any lotting decision to be made. Unless I am mistaken, “community” is not ascribed with a particular meaning in the statute.

The remaining provisions of this Part deal with the aftermath of a lotting decision. Section 67P allows for the land owner or a relevant secured creditor to request a review of a lotting decision after one year has passed (and thereafter on a yearly basis if they wish to review a review). Section 67Q allows for a review request to be withdrawn, but where no withdrawal happens Ministers then have three options: stick with the original decision; make a replacement decision; or buy the land in question (see below). Section 67R caters for the making of a fresh decision (basically in the same terms as previously, but with an additional requirement to speak to someone who (in their view) is suitably qualified, independent and to has knowledge and experience of the transfer of land of a kind which is similar to the land in question. Perhaps the main impact of a review though is that it unlocks section 67S: “Offer to buy following review”.

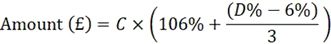

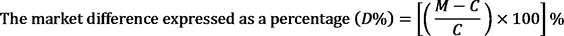

Section 67S provides a mechanism for state acquisition of land (for value). It lays out how Ministers may (but not “must”) offer to buy land following a review of a lotting decision, and importantly provides that this will only happen if Ministers are satisfied that the fact that the land has not been transferred since the lotting decision was made is probably attributable to the land being rendered less commercially attractive than it would have been because of the lotting decision prevented it being transferred alongside other land.

Should Ministers offer to buy the land in question, only a price set by the appointed valuer or by the Lands Tribunal (where an appeal is made against the appointed valuer’s price) can be paid; there is no room for horse trading. This valuation regime may be bolstered by regulations. Section 67T is also potentially relevant in relation to a purchase by Ministers, such that the owner (or secured creditor) can specifically request that Ministers buy the land. Ministers must then consider this fully in the usual way (i.e. are they satisfied the land is less commercially attractive etc.) and, if they decide against proceeding, give written reasons for that. Any Ministerial decision here is subject to appeal, again to the Lands Tribunal, but subsection (5) makes clear that even if the Lands Tribunal determines that Ministers are entitled to be satisfied that the test is met, all they need to do at that stage is consider making an offer.

Section 67U deals with an appeal against a lotting decision, and as noted above this goes to the Court of Session. I’m not immediately clear as to why the Court of Session is the appointed forum here, but it is. Section 67V contains compensation provisions, such that an owner of land (or a secured creditor) is entitled to compensation from Ministers for losses or expenses incurred in complying with the procedural requirements of the regime or are attributable to a potential transfer of the land being prevented or to a lotting decision stating that the land may only be transferred in lots. Regulations are to follow regarding this important matter, but for now it can be noted that Ministers are the first port of call to determine how to fully compensate someone, with the possibility of an appeal to the Lands Tribunal.

Finally for this new compulsory lotting regime, various “further provision” sections deal with the publicity of lotting decisions, the treatment of secured creditors, and setting out what provisions can be changed by regulation (namely what constitutes an exempt transfer, the land which is caught, and time periods relating to how long lotting decisions last for and when they can be reviewed). A new section 5 of the new Bill tweaks certain aspects of the 2003 Act to do with the making of regulations and decisions under the new regime.

Land and Communities Commissioner

I’ve already touched on the various roles of the new Land and Communities Commissioner, but for completeness I’ll mention that section 6 of the new Bill deals with the necessary administrative matters of creating this new office with the existing Scottish Land Commission.

The LCC is a bit like the existing Tenant Farming Commissioner. By that, I don’t mean that they have the same functions, but rather both of these offices are suitably specialised and as such cannot be categorised in the same way as the other five Land Commissioners.

Beyond the necessary changes to the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 to allow there to be this extra figure in the Commission, I will highlight a couple of noteworthy points in the new Bill.

First, to be eligible to be the LCC, the candidate is to have expertise or experience in land management and community empowerment.

Second, Land Commissioners must have regard to the exercise of the LCC’s functions (see below) when they exercise any of their functions in relation to large landholdings. This mirrors their deference to the TFC in so far as the exercise of their functions relates to agriculture and agricultural holdings (per section 22(4)).

Finally, new sections 38A, 38B and 38C of the 2016 Act set out the LCC’s functions, their ability to delegate, and the ability to appoint an acting LCC when the office is vacant. For completeness, the functions of the Land and Communities Commissioner are: (a) to enforce obligations imposed by regulations under section 44A [in relation to community-engagement obligations]; (b) to exercise the function conferred on the LCC by Part 2A of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003 [for the extended opportunity to register a community interest in land; (c) to collaborate with the Land Commissioners in the exercise of their functions to the extent that those functions relate to the functions of the LCC; and (d) to exercise any other functions conferred on the LCC by any enactment.

Part 2 – Leasing Land

As noted above, Part 2 relates to “Leasing land”. One might make a slight harrumph about agricultural holdings and small landholdings being lumped in with land reform more generally rather than getting their own nominate statute(s), but the precedent was set with the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 including such matters and here we are again.

Part 2 is subdivided into three chapters. The first of those chapters contains a single section, which provides a skeleton for a future model lease for an environmental purpose. We are also given a definition of an environmental purpose, but otherwise matters are left for regulations (and the model lease is supposed to be brought in within two years of the Bill receiving Royal Assent).

As I understand, one planned benefit of this model is that it should avoid any issues that might arise from people shoehorning non-agricultural activities into an agricultural lease (as agricultural leases must primarily be used for agriculture in order to ensure a tenant’s compliance with the lease). This new model will have a capped amount of agricultural activity (of less than 50% of the land use activity).

There is not too much more than can be said at this stage about this environmental purpose lease simply because without that model lease it is not clear what benefits this letting vehicle will bring to either landlord or tenant that could not be achieved with a common law (non-agricultural, non-residential) lease for a specific purpose. In fact, even with a model lease I am not clear what benefits there might be, but given the model lease (according to section 7(1)) is to be used “(wholly or partly) for an environmental purpose” perhaps it is envisaged that it will not be possible to contract out of some features of it.

Next, chapters two and three relate to small landholdings and agricultural holdings respectively. Small landholdings are also covered in the Schedule to the Bill.

I’m not going to go into the finer points of detail about the changes to small landholdings here. Instead, I’ll simply quote from the Explanatory Notes to give an overview of the changes.

Section 8 of the Bill introduces the schedule. This introduces a number of rights in respect of small landholdings for the first time: specifically, in relation to diversification and the right to buy. It also consolidates (i.e. restates in one place) and makes a number of policy changes to the current archaic law on small landholdings in relation to certain topics: specifically, in relation to rent, assignation, succession, and compensation. The law on renunciation is also restated with only minor consequential changes (arising from the removal of provisions about loans which no longer apply). As a result of all of these changes, the current law as it applies to these topics is disapplied.

Paragraph 94

One other point relating to small landholdings is that they are now to be brought within the purview of the Tenant Farming Commissioner. Some consequential changes are made to the parent legislation for the TFC accordingly.

The Policy Memorandum suggests (with reference to The Scottish Government Agricultural Census 2021) that there are 59 (fifty-nine) small landholders in Scotland, meaning in raw numbers terms these changes won’t have a massive impact (albeit clearly changes in the law will be important to parties with such a lease).

We then turn to agricultural tenancies (which I am using as a catch all term for the many tenancies governed by Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 1991 and the Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 2003 (both as amended)). Many of the important reforms as regards agricultural tenancies relate to the securest form of agricultural holding governed by the Agricultural Holdings (Scotland) Act 1991, although some provisions of the Bill will affect newer agricultural tenancies (e.g. in relation to tenant diversification, resumption of land by the landlord, and rent review). Crunching the numbers again, the Policy Memorandum tells us there are 3,821 secure 1991 Act agricultural tenancies, meaning they are not quite as endangered as small landholdings but they are not exactly ten-a-penny.

As to what these provisions will actually do, I am going defer to others who are dealing with such tenancies day-to-day before I career heelster-gowdie into this very specialised area. Hopefully expert practitioners might be moved to post something soon. I will try to offer some superficial coverage though, drawing on the Business and Regulatory Impact Assessment (at paras 4.5.2-4.5.11).

That BRIA content begins by noting that, “The provisions collectively encourage agricultural tenants to participate in sustainable and regenerative agricultural practices towards delivering the Scottish Government’s Vision for Agriculture.” It then goes on to highlight the various amendments in context, pertaining to diversification (so that the environmental benefit of a new activity can be included in a tenant diversification notice and in turn enable the Scottish Land Court to consider environmental beneficially diversifications), agricultural improvement (to facilitate tenant activities such as renewable electricity measures for on-farm energy needs, hydroponics or the creation of silvopasture), and good husbandry and estate management (which would allow practices that are apparently important to ensure access to future agricultural funding, such as by allowing tenant farmers to leave uncropped field margins and participate in a wider range of sustainable practices), plus related changes around waygo (to enable a wider range of activities to be included as factors to be taken into consideration in calculating any sums at waygo, and separately to introduce a set timescale for the waygo process). There are then changes in relation to resumption compensation (where a landlord recovers all or some of the let land from the tenant) and game damage compensation that a tenant can expect should such circumstances apply. Finally, the pre-emptive right to buy process for secure 1991 Act tenants is tweaked, plus a there is to be a new rent review scheme (which I won’t try to explain here). Intriguingly, this newest Bill removes a change to the registration process that was included in the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016, which would have (if it had been brought into force) removed the need for an agricultural tenant to register an interest. Otherwise, we await further regulations about this tenant’s right to buy, and I cannot really comment beyond that. The newest Bill also sweeps away the rent review regime that would have been brought in by the 2016 Act. Will the new provisions have more luck? That’s a question for another day.

All of this is also considered in the aforementioned Strategic Environmental Assessment of Agricultural Tenancies, Small Landholdings and Land Management Tenancy Proposals: Consultation Report. That assessment was, however, only based on 12 responses to a questionnaire, and thus must be treated with due care and attention.

One final point on such rural tenancies: a consolidation statute would be really nice, one of these days. I suspect consolidation is not a priority though.

What’s not in the Bill?

The consultation aired quite a few things that don’t appear in this Bill. There’s not much about a beefed up land rights and responsibilities statement, for example: the only reference to the LRRS is in relation to using it to inform any regulations made in relation to the community-engagement obligations of the owner of a large land holding. There’s not much on cross-compliance. There is nothing about recipients of Scottish Government land-based subsidies needing to be registered and liable to pay tax in the UK or EU. There is nothing about tax, albeit that might not be a surprise given fiscal matters were basically just tagged onto the earlier consultation. Now, it may be the case that certain matters will be picked up in a future Agriculture and Rural Communities Bill (which is alluded to in the recent SPICe Spotlight), so I won’t labour this point too much. Again, we must wait and see, although we can at least acknowledge the recent endorsement of the general principles of the Agriculture & Rural Communities (Scotland) Bill by the Scottish Parliament’s Rural Affairs & Islands Committee. and point to sections 7 and 13 of that Bill in terms of compliance with guidance and/or conditions.

What next?

Legislation at the Scottish Parliament goes through three Stages. Some evidence will be heard before a Committee, Reports will happen, and amendments will be proposed and voted on. Per my earlier comment, 2025 is the year that we can anticipate that this will be passed.